|

Here’s a challenge I see quite often while we’re on a client project involving mechanical design or CAD work. Does this familiar? Someone is tasked with designing a new sub-assembly or component for an existing product. As they get underway their work on face value gets the company to a conclusion where the design/ drawing is technically complete. As such, this person is able to check the proverbial box for ‘task completed’ and move on to the next assignment. While the work may have technically been completed, it often is done in a fashion which causes all sorts of problems down the road for the company, including other employees working on the same project within the same organization as well as their external suppliers. How is it someone can complete a design project satisfactory on the surface yet problems arise down the road with that very same design, which had been previously approved? Answer: the devil is in the details, or lack thereof, to be more specific. The reason why companies and or their respective employees experience this is because they aren’t following a formal and documented ‘gold standard’ for their product design practices. Simply put, they lack discipline with design fundamentals. As a result of a lack of design standards (and perhaps training) employees are left to decide for themselves how to complete a task which may get them to the finish line but the approach, process and details along the way can have wild variances and interpretations. While this may be commonplace and old news to many of you reading this article, the reality is the actual practice of designing a product with repeatable ‘gold standards’ is anything but common sense or consistent in the workplace. When our approach to design is fast and loose we experience the following:

When these issues show up it causes companies to reinvest dollars and resources into their work in order to move the project forward to get it to a point of where it can be properly advanced along the product development life cycle. This reinvestment is unnecessary and a huge time suck. We see this a lot when a medical device OEM has a contract manufacturer (CM) do some of their design work. In more times than I can count the work which is produced in this scenario is rough, limited with detail and documentation, almost never parametrically driven, and close to useless in other scenarios. Don’t fall for the trap of “we just need drawings.” While that may be the case in the moment, this will almost always cause you more work and funds down the road. For these reasons it’s vital companies implement a ‘gold standard’ in their design work which their employees and suppliers follow to ensure the work each party is facilitating makes it to the finish line in the same format, intent and approach. This unification of process increases the likelihood design work is done correctly while also ensuring future usage of said designs doesn’t require additional unnecessary iterations or complete redesigns. If implementing a ‘gold standard’ for your design and product development practices could be a benefit to your team or company, here are some of the key points to consider:

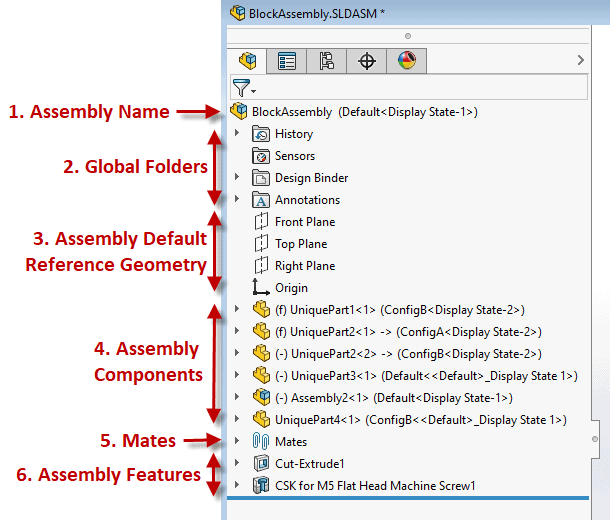

Example below: A well laid out Solidworks Assembly Feature Manager Design Tree If you, and or your company, lacks a ‘gold standard’ for your product design efforts you are inevitably wasting time and resources. This also has a direct correlation to a suppliers’ ability to help with outsourced work causing the overall project to be more challenging and lengthier than necessary (prototyping, manufacturing, etc.) While this isn’t a fun realization there is hope! Here’s how to fix it. Start right away by developing a best practice plan. This will help you and your team form an outline for what design practices and approaches are ideal for your product and technology, which aren’t, etc. From there setup a review plan to provide feedback on all work performed. Once the infrastructure of your new gold standard system is established you’ll want to asses the skills of your team and develop a training program which can be offered to both new and existing employees.

0 Comments

At the forefront of the medical device new product development (NPD) process we typically find a list of considerations we’re trying to address within our product all while coming up with a solution which meets marketplace needs. Talk to anyone in R&D, or downstream marketing for that matter, and you’ll commonly hear the list of ‘needs’ for a new product can seem never-ending. What you may find surprising is how often design for manufacturability (DFM) is not considered in the beginning of the development process. DFM is an important, and often overlooked, part of product development which involves designing a product in a way which makes it easier and more cost-effective to manufacture commercially. While embedding DFM into the process early seems like a logical part of the process, what plays out in reality is an NPD process that is focused on creativity and validating a technology yet can lack appreciation for the future state of the product and it’s foray into the market. So why is it companies may overlook incorporating DFM into the development process? For starters, many of us who design products on the front end, have little perspective, or perhaps no perspective on what it takes to actually produce a scalable product on the back end. Unless you’ve worked on a manufacturing floor or you’ve walked through an entire new product introduction (NPI) cycle, it’s easy to misunderstand all which goes into producing a product to bring to market. The design process also requires creativity and ingenuity in order to find new approaches, break common perceptions of technology capabilities, etc. It’s about ideation! Unfortunately thinking down the road about how it will be built for commercial purposes is “someone else’s problem”. To illustrate this point let’s look towards the automotive industry at a product we all know, which also happens to be a heavily regulated industry, like the medical device industry. If you have ever been to a large-scale automotive show, like the LA Auto Show in Los Angeles, CA, what you’ll see are concept cars on display to wow the eyes and entice the senses. Ironically, if those same concept cars ever got to production, you’ll find their characteristics which made the vehicle look incredible are often diluted down to features and benefits which consumers will accept and are cost efficient to produce. Case in point, the two images below shows a 2010 Chevy Volt electric vehicle. The top image is the concept vehicle – sleek, sophisticated, sharp lines, aggressive character and eye catching. Almost resembles a sports car. The bottom image is the production vehicle – commuter extraordinaire with features which are dull, less angular and more consistent with a car which will be manufactured by the hundreds of thousands. Concept vehicles have their place though – mostly to show off a company’s capabilities and satisfy egos. They just aren’t practical on scale. The truth is if Chevy produced at volume the concept version the average consumer wouldn’t be able to afford it. As a result, they round out the features, slap some plastic on it and Walla you’ve got a commuter vehicle fit for the masses at a price point which coincides with high volume sales. The medical device industry is no different. While industrial design is playing a much larger role today with device design, the fact of the matter is our industry struggles at times with over engineering products just like the auto industry. This can lead to a company losing sight of what the end user needs and wants, as well as if it can actually be manufactured to meet reimbursements. It’s for these reasons it’s important to consider design for manufacturing from the very beginning of the design process. If you do so, you stand to experience the following:

Considering DFM from the beginning of the design process is crucial for optimizing the manufacturing process, reducing costs, improving product quality, and ensuring a smoother path to market. It ultimately results in a more competitive and successful product with potential less risk downstream. The quickest way to overcome a business challenge is to get help from those who are experienced in besting your beast! The team at Square-1 Engineering is comprised of a variety of medical device technical and project management professionals who are subject matter experts in the areas of NPD, Quality, Compliance and Manufacturing Engineering. Learn more about how we can solve your work and project problems today to get you back on track!

Recently our firm took on a project which offered an interesting perspective and remainder having to do with the importance of thinking long term and planning accordingly. When you’re developing a product, regardless of which phase of the development cycle you’re in, it’s crucial to always consider the DFM (design for manufacturability) side of things. Otherwise, you could end up in a situation like our customer did below. Our customer had a novel approach to addressing a problem on the market which hadn’t been dealt with in years. The other companies and people in this space just keep doing the same thing over and over while accepting patient outcomes which at times were and still are mediocre. In here lies opportunity. Our customer hired a design firm to develop a prototype based off their concept to address this patient problem. What came of this partnership with the design firm was an incredibly neat, novel and quite frankly cool technology. Plus it looked awesome! The design firm, at first glance, hit it out of the park. Well done, chaps. The prototype was impressive. It was so impressive it even garnered a new round of funding, series B, for our client. All was good in the world. Right? Wrong. While the approach for this prototype was indeed cutting edge it failed to address a crucial area of the product development lifecycle – manufacturability. Our customer had a really cool product, and boy did it look cool in action, but unfortunately it couldn’t be commercialized due to its associated COGS (cost of goods sold) and manufacturing time per unit. Basically, what happened was our customer hired a design firm to develop a really cool looking product that couldn’t actually be manufactured because DFM hadn’t been taken into consideration. This is akin to what happens in the automotive industry all the time. A really cool concept is developed, often times to allow a company to flex its technological muscles yet what ends up being produced and available to the masses is quite different. (as shown below with this example of Chevy Volt’s Hybrid, side by side) Notice the different in the design elements and ergonomics. The concept looks stealth, sleek and modern. Almost like a Camaro. Who wouldn’t want to drive that car! Whereas the production vehicle is a dumbed down version, not nearly as cool looking, almost rather plain and forgettable. It’s now a commuter vehicle designed to do one thing, put on the miles and get you from point A to B. So why does this happen, where concept and production product are two different things? Often times the simplest explanation is that the cost (COGS) of building the concept to meet production volumes would be so high that it would far surpass the cost point which the product, or in this case, the vehicle needs to be sold at to be competitive on the market. No one is going to buy a non-luxury 4-door commuter car made by Chevy which costs $80,000 US. If the company kept to the original concept design and tried to manufacture that at high volumes that’s exactly what would happen. Few would be sold and the vehicle would tank in ratings and Chevy would lose money in the process. As a result, they dumb down the design and features to meet the needs of the target customer audience. In the medical device industry things work much the same way with one slight difference. Cost of a product per unit is most often based on what a company can get reimbursement approvals for. If you’re developing a medical device that relies on reimbursement to make money it’s absolutely crucial your COGS per unit are below the rate in which you can get reimbursed for, otherwise you won’t make any money. A professor of mine back in college used to say (and do so with a flair of arrogance that was most fantastic), “It’s economics. You can’t spend more than you make. Duh” Duh, indeed. So back to our story. Our customer is now left with a really impressive paper weight. They can’t manufacturer it in its current state and do so at a price that would allow them to make money. They’ve spent an incredible amount of time and money to be in a position that doesn’t allow them to move forward and get a product to market. When we were brought in to help the customer the story we learned along the way wasn’t unlike many others we’ve heard before. In fact, we see this all the time. Fortunately over a period of 6 months we were able to work with he customer to make some small design changes along with manufacturing process changes, in particular their test fixtures and work flow, to finally get to a point where the product could be ready for commercialization. What made this outcome come to fruition was the customer was very open to ideas and changes as this was critical to getting the product to a commercialized state. Key Take Away: If you’re developing a product, regardless of the industry or market you’re in, never take your eye of the importance of DFM (design for manufacturing). A novel, emerging technology that can’t be manufactured is basically a really expensive paper weight. Action Item: If you’re developing a product and are considering using a design firm or supplier to help you with that effort make sure you vet them to understand what their experience has been getting a product to market. Anyone can design something that looks cool. Designing something that can actually make its way to the market and ultimately the end user is another thing all together. Ask the supplier for examples of design work they’ve done which ultimately got to a full commercialized state. Once you have these details you can better determine if this company is the right fit for your needs. It’s important to recognize there are plenty of times where a company needs design help and it’s purely for the purposes of having a concept, not for the purposes of having a product on the market. It’s important to understand the differences between the two and where your needs are with your own product. Interested in learning more about the case study attached to this article? If so, click HERE.

About the AuthorTravis Smith is the founder and managing director of Square-1 Engineering, a medical device consulting firm, providing end to end engineering and compliance services. He successfully served the life sciences marketplace in SoCal for over 15 years and has been recognized as a ‘40 Under 40’ honoree by the Greater Irvine Chamber of Commerce as a top leader in Orange County, CA. Categories

All

Archives

July 2024

|

||||||

Visit Square-1's

|

|

RSS Feed

RSS Feed